Date: 10/08/2024

Author: Charles Ganbaatar.

Article Overview

The purpose of this article is to express my views through two management theories on managing incompetent employees. I will elucidate my observations about the management practice, identify the most realistic and practical leadership style and approach to deal with the incompetencies. In the following pages I will discuss two management theories and explain the differences, namely contingency theory and situational leadership theory. I will then address each of the following topics and demonstrate the desirable leadership style and approach in a diagram.

- Contingency Theory

- Situational Leadership Theory

- The Four Leadership Styles and Employee Maturity

- Occupational incompetence

- Lead incompetent employees

Contingency Theory was initially developed in the 1950s, by Fred Fiedler while he was conducting research studies analysing the effectiveness of leaders (IMSA, 2019). It paved the way for further contingency theories such as situational leadership. Fred Fiedler suggests in his Contingency Theory that an effective leader recognises various situations, assesses the situation and identifies the right leadership style to deal with that situation (Fiedler, 1964). In 1995, Fiedler, Ayman and Chemers suggested two main factors that would contribute to effective leadership and management: (1) leader attributes, referred to as task or relationship-oriented leadership style, (2) situational favourability and control (Fiedler, Ayman and Chemers, 1995). Relationship-oriented leaders are good at building rapport, synergy and managing potential interpersonal conflict. On the other hand, task-oriented leaders tend to be great at managing projects and organising teams to accomplish tasks. The contingency approach quickly gained in popularity in the 1960s and 1970s, contingency theorists disputed assumption that a single form of organisation is best for all circumstances.

Fred Luthans states in his research article The Contingency Theory of Management that relationship-oriented leaders would find it difficult to overcome operations problems adaptable to quantitative solutions and task-oriented leaders could not easily overcome employee behavioural problems (Luthans, 1973). The contingency theory is also an organisational theory claiming that there is no best way to lead people, organise a corporation and make business decisions. Instead, the best course of action is dependent (contingent) upon all situations. On the other hand, the neoclassical theorists suggested that decentralisations must be implemented for all situations and conditions, policies should be placed at the lowest level of government in order to encompass economies of scale (Marks & Hooghe, 2000). To put it another way, the trade-off between economies of scale to large jurisdictions and heterogeneity of people’s preferences is the core concept of neoclassical theory (Alesina & Wacziarg 1998), for instance, the country’s dictators do not care about the trade-off between efficiency and heterogeneity. Given economies of scale in taxation, dictators seek to maximise tax revenues instead of maximising the utilities of citizens (Alesina & Spolaore, 1997). In other words, managers who uphold neoclassical theories are not recognising individual choices with respect in their approach. The efficiency of neoclassical theory is therefore ambiguous and inappropriate for all situations. It has been criticised for neglecting key ingredients such as transaction costs, ideology, coalition and rulers’ private preferences. In practice, neither neoclassical nor modern structural organisation designs can hold up under all situations (Luthans, 1973). Bureaucracy cannot cope with dynamic situations and decentralisation cannot work well in cybernetic situations.

Although the contingency approach is discussed regularly in today’s organisational scholarship, some people see it as obsolete. Regardless of what assumption and expectation people might have, many of its key values and insights still underpin contemporary management or organisational research. Some researchers focus primarily on organisational structure, such as Joan Woodward. Who had made exceptional contribution to organisational theory that every organisational structure is contingent on the types of production technologies implemented (Woodward, 1965). James Thompson focused on open systems for complex organisations, his organisational theory offers a systematic investigation to answer why uncertainty is the major problem for complex organisations, and how to cope with it by understanding the essence of the administrative process (Thompson, 2017).

Leadership style on the other hand is the pattern of behaviours managers use to influence the behaviours of their employees as perceived by them, employees can also use similar leadership styles to influence their colleagues (Blenchard, Hersey & Kenneth, 1969). However, many people have wrong perceptions of their own behaviour and its impact on others. For instance, you think you are a people-oriented and kind manager, but your employees see you as an emotionless and hard-nosed person. They will instinctively act on their own perception of reality, not yours. Also, if managers and employees are unaware of their level of incompetence, they will subsequently fail to accomplish given tasks without realising their own inabilities.

I therefore believe that incompetent managers or employees are unable to adapt their style to fit requirements of the situations, the level of incompetence in all stakeholders hinders the likelihood of a task-oriented leadership style being shifted to a relationship-oriented leadership style; particularly when managing employees or dealing team members. Which is to say, any leadership style is ineffective to unskilled people. It would be an abortive attempt for incompetent individuals to become successful leaders or capable employees in any given situation. However, there are such incompetent leaders in charge of the organisations, and I will elaborate on this subject later. Regardless of the unforeseen situational factors or circumstances in the management, I feel that the ultimate goal of a contingency theory of management will be to match quantitative (task-oriented), behavioural (relationship-oriented) and systems approaches with appropriate situational factors. In the 1950s, Joan Woodward marked the beginning of a situational approach to management and organisation in general. She indicated that organisation structure and human relationships were mostly a function the technological situation (Luthans, 1973). In addition, situational leadership delineates readiness as the willingness and ability to take responsibility for controlling and directing their own behaviour (Hersey, Kenneth & Blanchard, 1988). When individuals are not at a level of readiness, they are not ready to utilise or adopt any basic leadership styles. For example, a gardener maybe at high levels of readiness for landscaping but cannot replicate the same abilities in a car mechanic’s job. The gardener will be unlikely to become a mechanic in a short period of time regardless of what trainings are provided, because the special skills of a mechanic are outside of the gardener’s circle of competence and vice versa. On the contrary, a company’s salesperson maybe at reasonably high levels of readiness for door-to-door sales but may not demonstrate the same degree of readiness in writing reports and advertising. The manager can adopt relationship-oriented leadership style and provide support on report writing and advertising training programmes with close supervision to bring up the salesperson’s level of competence.

Contingency Theory

Contingency Theory is based on the idea that the efficiency of a leader is largely dependent on the type of leadership style is utilised for a given situation in the workplace (Kuhn, 2007). It relies on the Least Preferred Coworker (LPC) scale developed by Fred Feidler to subjectively evaluate an individual’s attitudes toward their least favourable coworkers. For instance, the more positively you rate your least preferred coworkers, the more relationship-oriented you are. Conversely, the more negatively you rate them on the same criteria of the scale the more task-oriented you are. The LPC scale assumes that the relationship-oriented managers tend to rate their least preferred coworkers in a positive manner, while task-oriented managers rate them in a negative manner. Unfriendly or hostile employees preferably to be managed by the relationship-oriented leader, and they will be looked after in the team. It is advisable to put positive and friendly employees in the task-oriented leader’s team, so they do not clash with each other. The benefit of this theory is to help managers to understand what qualities they will need to succeed in different situations and managing different types of employees (Khurana & Nohria, 2010).

Situational Leadership Theory

It is based on the idea of adapting certain leadership styles to fit given situations. Situation leadership style can be altered and adapted according to the situation, whereas contingency theory does not have such options. Under contingency theory, managers either choose task-oriented leadership style or relationship-oriented leadership style. Situational leadership theory has directive and supportive behaviour dimensions which comprise the style of each leader. To choose which leadership style is appropriate for a certain situation, managers must analyse and process the situation and identify the needs and act accordingly. Situational leadership style is based on directive and supportive behaviours (Blenchard & Kenneth, 1985).

- Directive Behaviour:

The leader engages in one-way communication with close supervision, directs the employee what to do, where to go, when to do it and how to do it.

- Supportive Behaviour:

The leader engages in two-way communication with minimum supervision, actively listens, provides necessary support and encouragement, facilitates interaction and involves employees in the decision-making process.

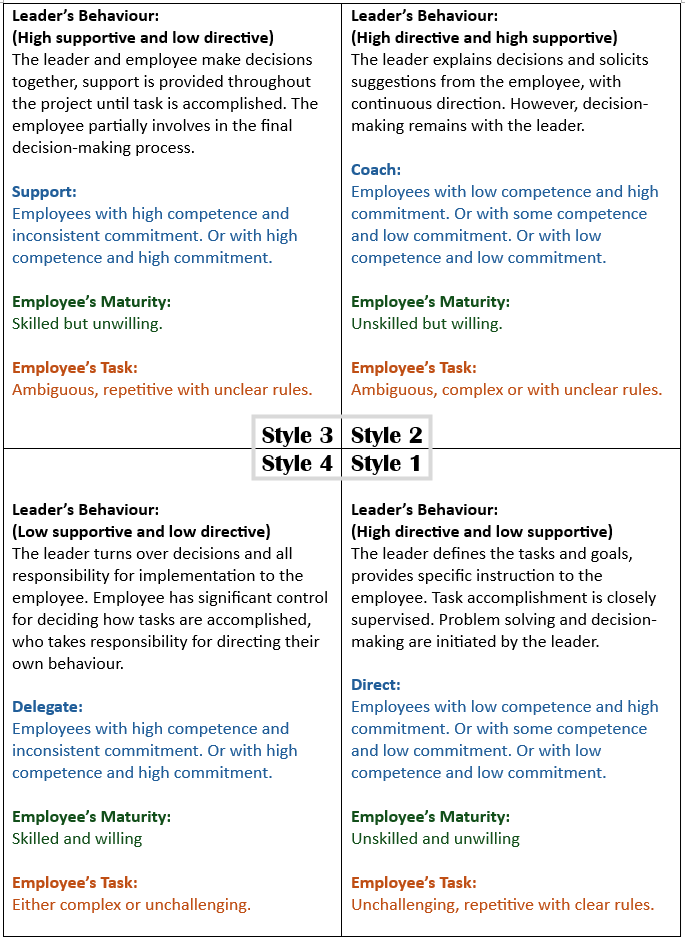

Figure 1. The Four Leadership Styles & Employee Maturity Model

(Edited by author)

Notes:

Interchangeable styles

Skilled and unwilling employees under “Style 3” can also be managed by “Style 1” leaders, because employees who have a perceived lack of intrinsic desire to do their job are more volatile and deemed to be less reliable. Therefore, directive leadership style can assert more authority to ensure completion of the given tasks.

Grey areas

There is a reasonably high possibility that many employees will eventually become skilled and unwilling to do their job after a long period of time; depending on the effectiveness of leadership styles being utilised, changes in workplace culture or during organisational restructuring process etc.

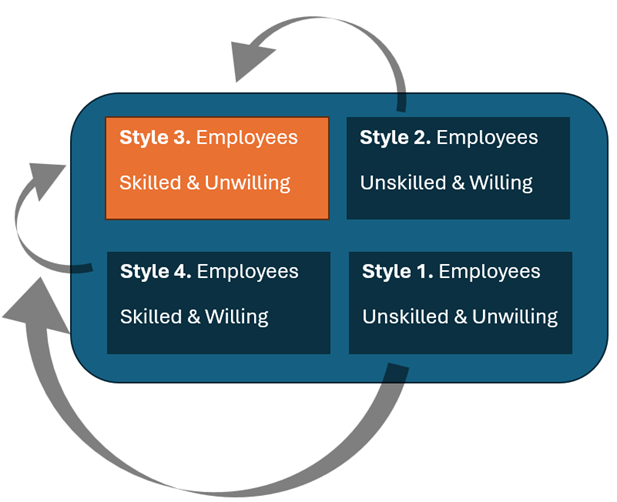

Figure 2. Tenancy for Style 1, 2, and 4 employees to progress and move into Style 3.

Occupational incompetence

Ignorance is bliss. Many of us never realise that we can reach the level of incompetence in the workplace rather quickly. We continuously keep ourselves perpetually busy and expect to remain happier, healthier and receive those “well-deserved” vertical promotions faster, advance up the corporate ladder and fulfil our crave for progression. At the same time, in our confidence and sophistication we shrug aside the immoral conduct, incompetent bosses, employees, corrupt business practices and incoherent executives. Much Incompetence appears to be creeping into all levels of every organisation in present day hierarchical systems, such as government organisations, nongovernmental organisations, political and educational systems. As stated by Laurence J. Peter in his 1969 book The Peter Principle, in an organisation every employee tends to rise to their level of incompetence, and every position is likely be occupied by someone who is incompetent do their job (Peter, 1969). Once employees rise to the level of incompetence, they are no longer productive and likely to become unmotivated. Peter has also mentioned that employees with good performance are inevitably promoted to the point where their performance is no longer satisfactory, those employees then tend to remain in positions in which they are incompetent. Here are some typical examples of incompetent managers and employees I have observed and obtained over the years:

Occupational incompetence

1. Daisy is a workplace administrator for a government organisation responsible for the well-being of youth in the country, she has a bright personality, a good level of resilience and she gets on well with others. Daisy is responsible for the administrative needs of her social worker colleagues and maintaining administrative functions, such as word processing and dealing with front counter enquiries. “I like Daisy, she has a bubbly personality,” says the site manager. “She is pleasant and agreeable and good at filing, ordering stationery and printing documents.” When a senior administrator leaves the job, Daisy is successfully promoted to the senior position. She quickly finds herself in difficult situations, because she constantly fails to coordinate with off-site social workers and process their enquiries in a timely manner. Before her promotion she does not have to deal with enquiries from off-site social workers or after-hour staff members. Now she cannot keep up with an unrelenting work pace and fails to take prompt action to deal with critical scenarios. Complaints poured in from social workers and after-hour staff. Daisy continues to perform her duties like a junior workplace administrator and forget about her other senior-level duties. Daisy, a competent workplace administrator, has become an incompetent senior administrator.

2. Margaret is an animal control officer; she is exceptionally intelligent and fervent. Soon she rises to senior animal control officer. In this position she shows outstanding investigating skills and ability to deal with dog seizures, complaints related to dog attacks and roaming stocks etc. Managers have strong faith in her ability and work ethics, Margaret gets promoted again to a team leader’s position. But now her love of animals and her perfectionism become liabilities. She micromanages her animal control officers’ dog-attack jobs, watches her officers’ actions closely and provides frequent criticism of her officers’ work and their lack of compassion. As a team leader she fails to maintain a positive public image of the organisation, as she gets emotional over animal mistreatment. She finds it difficult to craft media releases and shape public perception of animal control officers in the local communities. Margaret cannot get on with her fellow officers or build rapport with external agencies. She was a competent officer but is now an incompetent team leader.

3. A district Court site manager Nancy gets promoted to an area service manager to oversee the operations of three district Courts. Nancy’s seniority is being the main reason of her promotion, she also does not get on well with two of her Deputy Registrars in her old office. So, her promotion to a service manager’s role killed two birds with one stone. She is now out of her old office and managing two more offices. However, whenever there is a workplace conflict or a complaint from her Court staff, she fails to utilise conflict resolution strategies to resolve conflict quickly. Instead, Nancy has a habit of ignoring workplace conflicts and letting them miraculously go away. She proves incompetent as a site manager or a service manager, she will obtain no more promotion.

4. George is a residential support worker at a drug and alcohol rehabilitation facility, he assists residents with daily tasks, overseas individual treatment plans and supervises residents’ interactions and behaviours in a residential setting. Because of George’s lived and clinical experiences, he is a great listener and conversationalist. Many residents enjoy talking with George and sharing their stories while going through drug and alcohol addiction treatment. Geroge is soon asked to work with a small group of four male residents, help them to maintain long-term sobriety by supporting them through 12-step facilitation and off-site AA meetings. But his dedication of helping people have now become a hindrance to the completion of his duties assigned by his supervisor. He gets carried away in conversation with one or two residents, no matter how busy the facility maybe. “I will get to it after talking with the residents,” he says. He will not start helping others until he is done talking with the residents, he feels some need more assistance than others. George’s inability to set boundaries and use fair and consistent expectations make him an incompetent residential support worker.

5. Lance and his wife Sarah own a Funeral Home in a small town, Lance takes care of the operational side of the business and Sarah looks after the financial side. Lance provides a high-quality essential service to bereaved families, guiding the family through the funeral process and advising them different options. He communicates clearly and work confidently. Lance tries to avoid work overload and hires a young man as his assistant to help him with hospital transfers and funeral arrangements. Lance is a perfectionist and likes to correct small errors the young man makes, cares too much about minor details such as which pen goes into which pen holder, the hearse must be parked 15 centimetres away from the wall etc. He micromanages every task that is given to his assistant, to the point the young man thinks he is not being trusted or respected. His wife is aware of his pedantry but encourages his micromanagement, she believes it protects their family business. Lance fails to create trusting relationship with his assistant and does not recognise his employee’s talents and hard work. His assistant resigns after two months. Lance is a good funeral director but an incompetent business owner.

Lead Incompetent Employees

As previously mentioned, and indicated in Figure 2, most employees tend to become skilled and unwilling at some point in their career. In other words, they gradually become incompetent in the workplace and incapable of carrying out their normal duties. Regardless of what leadership styles you choose to motivate or help those incompetent employees to get back to the required standard, they will not corporate. They might even indirectly avoid responsibilities and try their best to prevaricate. In most cases, those employees are unaware of their level of incompetence. Such as the workplace administrator Daisy from the first example, who has unknowingly reached her level of incompetence as a senior administrator.

Since you as a manager cannot fire anyone who is simply incompetent, you will be responsible to create compounded effort. You must adopt task-oriented leadership style with defined boundaries between you and your employees and set clear paths. You also need to be more directive and less supportive in order to cut out any unnecessary tasks and make sure meeting the deadline is the primary objective, anything that deviates from that is a distraction or a maladaptive solution. Your job as a manager is to provide direct instruction, outline processes, set deadlines and delegate effectively and achieve results quickly. When dealing with incompetent employees, you need to be agile and quick to adjust to new situations and make immediate decisions when required. Relationship-oriented leadership styles will not work efficiently on incompetent employees. Task-oriented leadership style can also help to increase incompetent employee turnover rate, you want to keep good workers and let go the lousy ones. Incompetent employees can spread like cancer in a healthy organisation, and there are no cures for any kinds of cancer, but there are treatments that may cure the organisation.

References:

Alesina, A. & Spolaore, E. (1997). On the number and size of nations. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 1027-1056.

Alesina, A. & Wacziarg, R. (1998). Openness, country size and government. Journal of Public Economics, 69, 305-321.

Blenchard, K., Hersey, P. & Kenneth, H. (1969). Life cycle theory of leadership. Training and Development Journal.

Fiedler, F. (1964). A Contingency Model of Leadership Effectiveness. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 1, 149-190 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0065260108600519

Fiedler, F., Ayman, R. & Chemers, M. (1995). The contingency model of leadership effectiveness: its levels of analysis. Leadership Quarterly, 6(2), 147-167.

Hersey, P., Kenneth H. & Blanchard, K. (1988). Management of Organization Behaviour: utilizing human resources. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

IMSA (2019). Leadership Education and Development. IMSA. https://digitalcommons.imsa.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1016&context=core

Khurana, R. & Nohria, N. (2010). Handbook of leadership theory and practice. Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation.

Kuhn, S. (2007). An Overview and Discussion of Fred E. Fiedler’s Contingency Model of Leadership Effectiveness. Librarian Publications, 13, 1-10.

Luthans, F. (1973). The contingency theory of management: a path out of the jungle. Business Horizons, 67-72. https://edisciplinas.usp.br/pluginfile.php/7948405/mod_resource/content/3/Luthans%20-%20THE%20CONTINGENCY%20THEORY%20OF%20MANAGEMENT.pdf

Marks, G. & Hooghe, L. (2000). Optimality and authority: a critique of Neoclassical Theory. Journal of Common Market Studies, 5(38), 795-816.

Peter, L. (1969). The Peter Principle. William Morrow & Co.

Thompson, J. (2017). J.D. Thompson’s Organizations in Action 50th anniversary: a reflection. In B. F. Maria & M. Giovanni (Eds.). Bologna: TAO Digital Library. https://amsacta.unibo.it/id/eprint/5737/1/ThompsonAnniversary.pdf

Woodward, J. (1965). Industrial Organization: Theory and Practice. Oxford University Press.